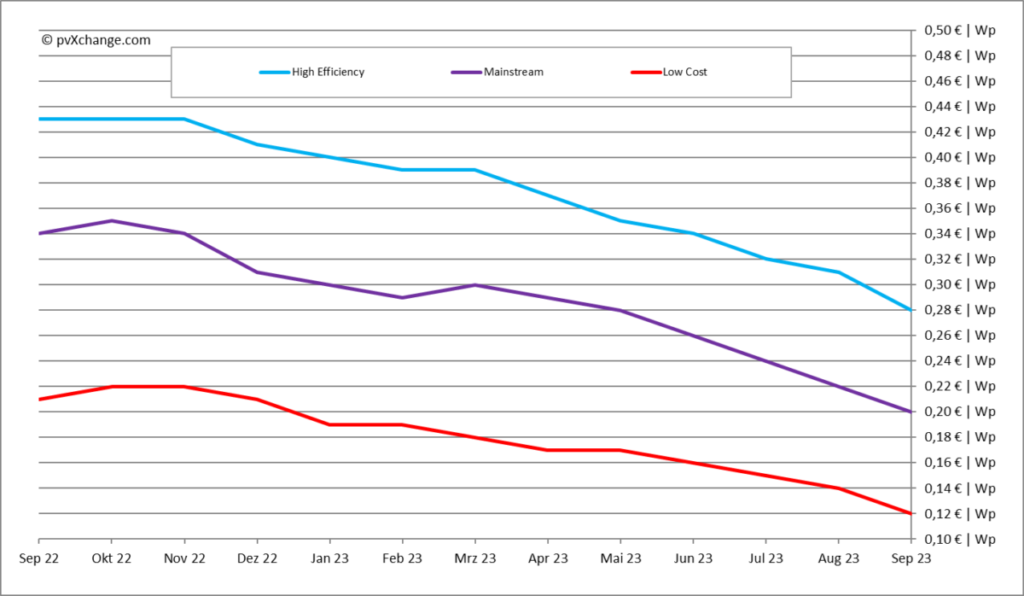

We have all been wondering for a while: How much lower can the prices of solar modules drop before they hit rock bottom? All prices have dropped again this month, so it looks like there is still room for more drops.

In general, prices have gone down by about 10% across all module groups. This is the first time in the history of photovoltaics that panel prices have dropped so quickly. The prices have been below the all-time low of 2020 for about a month now, and they are even lower than what most makers pay to make something. It looks like making money isn’t going to happen anytime soon. For many of them, it’s now just a matter of avoiding harm or even staying alive.

How did we get here, and what is causing this trend that hurts itself?

First, it’s important to note that module prices went up by more than 50% from October 2020 to October 2022. This wasn’t because of new technology, but because of a lack of supplies caused by the pandemic and a rise in demand at the same time. In the end, many people in the solar market made a lot of money, but customers lost out. Prices for solar systems had been higher for a long time until not long ago. Recently, everything has changed, which means costs will have to go down. But the speed and intensity of this change surprise even people who have been in the market for a long time.

Since there have been shortages for the past two years, a lot of installers and suppliers made big predictions and bought new goods like there was no tomorrow. The makers, who were mostly from Asia, responded by making their powers bigger. Global production capacity is usually 30% to 50% higher than what is actually expected to be needed. This way, changes can be quickly made up for. After that, the production lines are turned up or down depending on what is needed. These days, though, this process has gotten a little out of hand because many makers had to quickly switch from making cells and modules with p-type PERC technology to n-type TOPCon because of issues with property rights in some areas. It was not possible to sell certain items in all countries, so new capacities were built for ToPCon without changing the old ones or regularly shutting them down.

In the long run, things looked good because the prices of traditional energy sources were thought to stay high. Unfortunately, European lawmakers were very good at quickly changing old fossil fuel sources with new ones, so the pain of energy prices going through the roof went away very quickly. Plus, the pandemic seems to be over for good, and now the normal European can move without any problems. Many people who were planning to invest in solar systems are now hesitant to do so, in part because of the high cost of living. Even though loan interest rates keep going up, that doesn’t make the choice any easier. All of these things have led to a drop in demand, and the photovoltaics industry is still in the middle of September and hasn’t fully recovered from the summer slump.

Solar power is becoming less popular very quickly, which means that installers and project managers can’t fill their order books, and pre-ordered modules and inverters can’t be supplied on time. More and more things are piling up at warehouses for both makers and retailers. 40 GW to 100 GW of units that haven’t been bought yet are said to be sitting in shops in Europe, mostly around Rotterdam. It’s almost hard to figure out the exact amount. There are, however, already enough units in Europe to last for about a year. This is enough to give you an idea of how big the problem is. It takes up a lot of room and money to store these items, so losses are growing while sales chances are shrinking. As the pressure builds, the landslide will finally start to fall, and the first sellers will start selling their modules for less than what it costs to buy or make them. Competitors have no choice but to do the same, which starts the downhill process.

Now, you might think that if prices go down, demand must go up. A lot of the time, buyers and end users haven’t heard about the current price level for products yet. A lot of providers still have too much of the old product, which they bought for more money. It’s also just starting to lose value, which is why the price drop is getting worse every month. A lot of people still think they can get away with a black eye. But there is a very high chance of being stuck with the old goods. People who are interested in photovoltaics also keep a close eye on prices and look at different deals. This is why a lot of end users are waiting for the prices to go down even more before they place an order.

Now everything is up to where the journey takes you. Just how low do prices need to go before demand goes up again and everything is equal?

In China, the factories are already shutting down. This year, up to 50 GW will be built in the country, on top of the 80–90 GW that have already been put in. Still, even if no new modules came from China, it would still be months before the stack of modules was cleared. A lot of the modules that are kept are also made with PERC cells, which are less efficient than modules that use the newest technology. I don’t think these are good for strongly growing local demand. In places other than Europe, where people are glad to find cheap solar panels, these items are more likely to be used. A good price level can only be reached in the market again, in my opinion, once the current oversupply of modules can be cut down. At that time, though, the market is likely to have changed, and some people who are in it will lose their jobs.